Little Stories Little Prints, a 1916 Commemorative Project through Printmaking, presented and exhibited around Ireland 2016-2018

Almost fifty Printmakers from eight Printmaking studios around Ireland accepted an invitation to participate in this project, which aimed to create awareness of little known events or incidents during or around the time of the Easter Rising in 1916. Through a variety of organised events the artists were encouraged to research incidents and aspects of life at the time of the Rising and to create little prints in response to their research.

The Project was supported by the Kildare County Council Arts and Library Services as part of the decade of commemorations.

Pamela de Brí A Terrible Beauty “One of the most striking and enduring symbols of the rebellion, were the ubiquitous barricades. They were assembled with variety and ingenuity.” Joe Good from the Kimmage Garrison told of one constructed with an entire stock of a bicycle warehouse. Another was made completely of marble clocks. Captain Tom Weafer used huge rolls of printing paper from the print shop of the Irish Times to make a barricade across Abbey St. “It was a formidable obstacle, until a stray artillery shell hit the Irish Times building and the rolls of paper caught fire, carrying the fire across to the other side and rendering all the posts in Abbey St. untenable. This was, in fact, the cause of the greatest swathe of destruction in Dublin.” To add to the drama, a group of looters raided a shop nearby where they found and set off its content of fireworks. (From Easter 1916 by Charles Townshend)

Pamela de Brí No Women Having read quite a number of different angles on the Easter 1916 uprising, focus in 2016 seems to be, at last, on the varied role of women over and after the period of rebellion. Witness accounts given to the Bureau of Military history are now available for all to read online. While accepting it was a different time, with different social mores, distinct class systems with their own hierarchies and habits of poor interaction and communication it is strange how the role of females, with minor exceptions, was completely ignored even by the 1966 celebrations. Most of the leaders saw the value of working alongside women but one or two simply refused to allow them near their area of command. The most high profile of these is Eamonn DeValera who refused to have any women under his command in Bolands Mills. Even when Elizabeth O’Farrell arrived with a note ordering to surrender, he told her that he only takes orders from his commanding officer who was male. The title of the print is taken directly from the first sentence of the Proclamation and is subverted.

Brian Barry The Wharfedale Press The 1916 Proclamation bill was printed on a Wharfedale printing press in Liberty Hall by Christopher Brady, working with the compositors Michael Molloy and Liam O’Brien. The men completed the task, demonstrating fine resourcefulness given the dangerous and challenging circumstances involved. They had only enough characters to set half the type, which meant that the proclamation had to be printed in two halves. This effectively doubled their workload. The original version shows evidence of where they were forced to place a character or two from a different font in the body text and alter or touch up some letters in the bold heading text. The printing press was said to be a temperamental machine and it required constant attention during the process. The Wharfedale press is graphically represented in my linocut, constructed with type characters from the proclamation. It is in tribute to the men and the machine involved in its production.

Alice Beresford. I'll Shoot Eoin McNeill In the late hours of 23rd April 1916, a furious Countess Markievicz was admitted to the Machine Room in Liberty Hall. Brandishing what looked like a telegram she said to James Connolly: “I will shoot Eoin MacNeill”, James Connolly replied: “You are not to hurt a hair on MacNeill’s head. If anything happens to MacNeill I will hold you responsible”. The telegram in question was one of a several handwritten letters sent to Commanders across Ireland cancelling manoeuvres planned for that day. MacNeill, upon hearing of Roger Casement’s arrest after being caught trying to bring German arms ashore in Kerry, felt an uprising was a fruitless task and took it upon himself to try and cancel it. Christopher Brady who was a staff printer on the Workers Republic Newspaper, which was printed in Liberty Hall, told this account of Countess Markievicz. He had been commandeered by James Connolly to print the Proclamation. His witness account was told to the Bureau of Military History in 1952.

Alice Hanratty Dundalk Battalion Seamus Hanratty. Printer. Irish Volunteer. 4th Northern Division. Dundalk Battalion. “A” Company Mobilized Dundalk Easter Sunday 23rd April 1916. With comrades marched for Dublin. Area of Castlebellingham, Hill of Tara, Rathoath, Slane awaiting orders. Arrested. Held Slane Castle. Sentenced and imprisoned in Wakefield, Wormwood Scrubs and Frongoch. Released 24th December 1916

Andrew Kilty The girl that kept everything under her hat Margaret Skinnider, the girl that kept everything under her hat! Literally! That is where she kept the detonators for the Volunteers and the messages for delivery around the countryside, sometimes dressed as a boy. You could say that she was the first lady assassin in Ireland, maybe the first female assassin in this part of Europe. She was fearless when it came to battle, as she fought in Dublin in the Easter Rising. She was the only woman to have come away with an injury. She was also a teacher. Margaret Skinnider was one of the key women, if not the only female sniper, in the 1916 Easter Rising, as a member of the then IRB. She was born in Glasgow on 28th May 1892 of Irish parents. She was a member of a ladies rifle club there, which was set up to defend the British Empire. Ironically that backfired on Britain. She got mentioned for bravery. Margaret Skinnider was also a member of Cumann na mBan. To this day there is not a lot known about the roll of women in the fight for Irish freedom.

Angelina Foster Despatches During the Rising many women acted as dispatch carriers, scouts and snipers. In the days leading up to Easter 1916, Kathleen Clarke tasked Sorcha MacMahon with compiling a list of reliable girls. These girls then travelled the country handling key intelligence. Máire Deegan cycled from Gorey, Wexford, with dispatches for the 1916 leaders braided into a bun in her hair. Chris Caffrey was arrested, stripped and searched by British soldiers, but by then had eaten the dispatch. Other dispatchers were Min & Phyllis Ryan, Ina Connolly-Heron, Julia Grennan, Elizabeth O’Farrell, Margaret Skinnider, and Molly O’Reilly (who was just 15 years old when James Connolly asked her to raise the flag over Liberty Hall). Catherine Byrne sent by Pearse to the Four Courts also hid messages in her hair. All these women left their garrisons under the deadliest of fire. Early 20th Century Ireland had a vibrant women’s equality movement, cemented by the roles they assumed in 1916 and subsequent years.

Ann McKenna A Time and a Place In the print ‘A Time and A Place’, I’ve tried to capture a sense of peering back at a distant time… The scene is meant to be reminiscent of the tenements of Dublin and the view is from the dingy shadows of a hall that conceals its inhabitants…bringing the viewer out in to the street where daylight shines and children and other figures are going about their morning… The morning of Monday 24th April 1916 promised a beautiful Spring day. For many, and most particularly children, their cares were not of rebellion or politics and yet their lives played out - like so many “walk on” roles on the stage of Irish history.

Anne McDonnell Grace This piece commemorates the love of two passionate people and one of Ireland’s greatest romances. It relates to the marriage between Grace Gifford (artist and illustrator) and Joseph Plunkett, on the 3rd of May 1916, just hours before Plunkett was executed for his part in the 1916 Rising. They had met when Grace’s friend brought her to the opening of a new bilingual school in Ranelagh, Dublin in 1913. There was no electricity at the ceremony and so was held by candlelight. No friends or relatives were allowed to attend so two British soldiers acted as witnesses. Twenty other soldiers lined the corridors with bayonets. Once the service was over Plunkett was taken back to his cell. A few hours later Grace was allowed to see him for ten minutes. In 1949 Grace produced a witness statement: “When I saw him, on the day before his execution, I found him in exactly the same state of mind. He was so unselfish, he never thought of himself. He was not frightened, not at all, not the slightest. I am sure he must have been worn out after the week’s experiences, but he did not show any signs of it - not in the least. He was quite calm. I was never left alone with him, even after the marriage ceremony. I was brought in and was put in front of the altar; and he was brought down the steps; and the cuffs were taken off him. There would be a guard there, and you could not talk. …… I was just a few moments there to get married, and then again a few minutes to say good-bye that night; and a man stood there with his watch in his hand, and said: ‘Ten minutes’”. (Source Kilmainham Tales)

Barbara Hannigan Buy a Revolver Women played an integral role in the military campaigns during 1900-1923. In return, they demanded suffrage on equal terms and their sexes inclusion in politics. These demands were granted in the Constitution of 1922. “Buy a Revolver” is based on the accounts of women volunteers who were taught how to use a gun by Countess Markievicz. I was interested in the huge risks that the women were taking, the stark contrast between them shooting guns compared to their normal daily life. In a speech in 1909 Markievicz proclaimed that women needed to change their mode of dress to a more efficient one and learn to handle weapons rather than relying on men for their safety. She calls for women to: “Dress suitably in short skirts and sitting boots, leave your jewels and gold wands in the bank, and buy a revolver. Don’t trust to your ‘feminine charm’ and your capacity for getting on the soft side of men, but take up your responsibilities and be prepared to go your own way depending for safety on your own courage, your own truth and your own common sense, and not on the problematic chivalry of the men you may meet on the way….”Markievicz was tried for treason and sentenced to death. However, her sentence was commuted due to her gender. Surprisingly she did not appreciate this as she resented being discriminated against because she was a woman.

Bernadette Madden The RHA Burns In 1916,The Royal Hibernian Academy had been nearly one hundred years in its specially built gallery in Abbey Street, Dublin. Endowed by the RHA`s second President, architect Francis Johnson, the large and imposing building contained not just exhibition spaces for painting and sculpture, but also drawing schools and an apartment for the Keeper of the Academy. Over the Easter weekend of 1916, during which the RHA`s annual exhibition was taking place, the British gunboat “Helga” shelled the GPO and the area around it. The RHA building caught fire and was quickly destroyed. The Keeper, who was on the premises, managed to save some objects including the Royal Charter but almost all of the books, pictures and academy records were burnt, as were all the works in the annual exhibition. The RHA was eventually compensated for its losses…. leading to a wry comment from one of the academicians that it was probably the one and only time that all the artists showing in the annual exhibition got paid for their work!

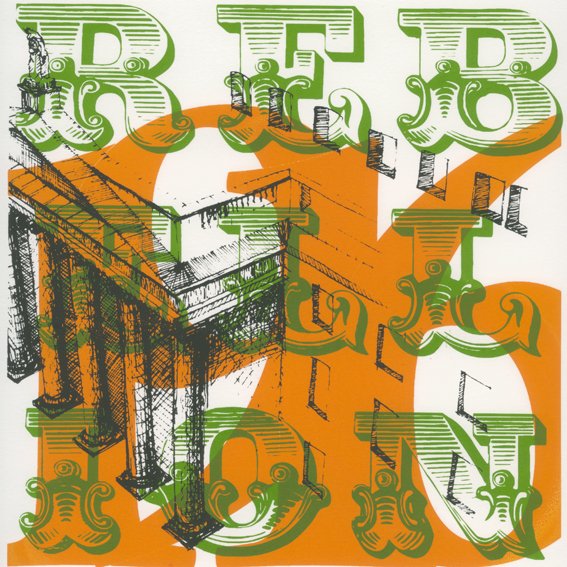

Brian Fitzgerald Rebellion My print explores the idea of the print as a form of communication, the role print has played in history and the strategic importance of the General Post Office played in the Easter Rising, through the use of typography, layering and colour. Print has taken a strong political role over the course of history as a way of mass communication and by disseminating ideas to a wide population. TV and the Internet have largely taken over this role in recent history but the visual element still remains core. In the Rising of Easter 1916 the GPO became the central headquarters of the rebel forces. A question I have always had was why not make their way to Dublin Castle to set up headquarters and declare Ireland a Republic from the place of British governance? Strategically, the GPO was hugely significant at the time as it was the centre of communication not only in the country, but with the world outside of Ireland, Germany in particular. The idea was that, if the rebellion was successful, to internationally declare Ireland an independent state that was engaged in battle and become a front line theatre in World War 1. The belief was that allegiance between the rebels and German forces would help swing fighting on the front lines of Europe in favour of the Germans after which the Irish fighting with British Units would down arms in support of their countrymen and women back home thus giving German forces the upper hand in battle.

Brian Lalor Raising the Flags, noon 24th April 1916 Despite the fact that there are many photographs of the Irish Citizen Army and the Irish Volunteers drilling or on manoeuvres in the months leading up to the Rising, when the insurrection actually took place, nobody thought to being a camera into the General Post Office or the other revolutionary outposts, depriving historians of any visual record of the events as they enfolded within the various garrisons. A seminal moment in the course of Easter Monday was the raising over the GPO of the various flags carried by the participating forces, an event as significant as the reading of the Proclamation to a bemused group of passers-by on Sackville Street. There is not much agreement as to who raised which flag so the image shows the Volunteers’ ‘Irish Republic’ (the tattered original is on display in the National Museum at Collins Barracks), the Citizen Army’s ‘Starry Plough’, and the ‘Tricolour’, the unofficial Irish national flag since 1848.

Brian Lalor The Aftermath, 1916 Following the raising of Martial Law, a month after it had been imposed on 29 April by General Maxwell, commander of the British forces, and the clearing of rubble and barricades from the streets in the Sackville Street area, Dubliners flocked to see what had happened to their once-beautiful city. They came in their thousands, every day, to gape at the ruins and reminisce about what had stood where. Men, women, children, entire families in trams, cars, carriages and horse traps, on foot and on bicycles, they arrived to gaze at the familiar, transformed in a week of warfare from a thriving metropolis into a ghost town. There is something about the crowds in the contemporay photographs from 1916 that suggests tourist flocking through the ruins of Pompeii, marvelling at the relics of a vanished race while attempting to comprehend something of the violence that created such hardly credible devastation.

Bríd Ní Rinn Capall ag éisteacht Working horses in the town or city, trained to stand still and wait, use the time to drop the head, relax one hind leg and have a nap. But not this one. The cart had been commandeered by the insurgents to make a street barricade. It is strange for the horse to be left unattended like this, still in harness but without the dray. He can hear gunfire in other streets, a very scary sound that he has never heard before. He shifts uneasily on his feet, flicks his tail and raises his head and tries to see as much as his winkers will allow him. I do not know what happened to this horse who had been driven up from Co. Kildare that day. But sadly we know that the driver was caught and killed in crossfire later in the evening. He had insisted in trying to retrieve his cart in spite of shouted warnings from both sides. It would seem that he understood warfare as little as did his horse.

Bríd Óg Norrby A Tragic Mistake Cesca Chenevix Trench was born in 1891 into a Unionist clerical family. She became a staunch Nationalist and changed her name to Sadhbh Trínseach. She studied art in Paris and began to draw political cartoons in support of Home Rule. She also designed Celtic costumes and posters for the Gaelic League, saying that she was in art school “to learn to compose a picture of Ireland”. Sadhbh was swept into an active role in Irish Politics and Cumann na mBan. When the Easter Rising began on April 24, 1916, she joined the other auxiliaries in St. Stephen’s Green. The following day she delivered First Aid supplies to the headquarters at the GPO, and then withdrew to Killiney Hill. In her diary, she wrote of the Easter Rising as a tragic mistake. She gives an authentic idea of the confusion and lack of information that characterised the event. She feared that she would be arrested for her involvement, but nothing happened, despite the enormous numbers being arrested. After the Rising, Trench continued her spirited support of Nationalism. She was a prolific artist in oil and pastel and painted many portraits of nationalist figures. Tragically, the October after marrying Diarmuid Coffey in April 1918, she caught the Spanish flu and died aged only 27. This is Sadhbh’s view of Dublin as she looked back from Killiney Hill on that day in 1916.

Charles Hulgraine A Greek Tragedy While viewing the events in the GPO Dublin 1916 a young Michael Collins said they had the ‘air of a Greek tragedy’. The rebels, in true unselfish acts of bravery and heroism, snatched the dying embers of Irish nationhood for future generations to live in a Republic but it was the character of the leaders during and immediately after the Rising that ensured its permanence. Their HQ was chosen more for its dramatic than military location deep in the symbolic hub of the capitol. Pearse, Plunkett and McDonagh were poets, playwrights and theatrical producers who deported themselves as if in the last Act of a tragedy, casting themselves as sacrificial heroes, modelled on CúChulainn. McDonagh with his sword, stick and cloak and Plunkett with his Celtic rings and bracelets. Politics and literature seemed to intersect at every stage of the proceedings and the oration of the Proclamation among the classical ionic columns of the GPO was histrionic. Even to his admirers, Pearse was a ‘bit of a pose’ - he branded an ancient sword right through a week of intense guerrilla fighting and insisted on handing over his sword in surrender to the victor at the top of Moore Street - a gesture of a bygone heroic age. (Kiberd - The Ireland Institute)

Claire Halpin Arbour Hill Plot On the orders of General Maxwell, 14 leaders of the Rising were executed from 3-12th May 1916. The bodies of the executed men, certified dead, a name label pinned to their breast were brought to Arbour Hill in a horse-drawn vehicle where a mass burial plot had been dug in the prison yard. Maxwell was determined that the bodies of the executed men would not be released to their families – he feared that “Irish sentimentality will turn those graves into martyrs’ shrines to which annual processions etc. will be made. [Hence] the executed rebels are to be buried in quicklime, without coffins”. A British Army officer witnessing the burials made a sketch noting where the bodies were placed in the grave. This sketch is in the National Archives in London. I became aware of this sketch through a tour of Arbour Hill with historian Paul O’Brien. I was struck that a drawing of such significance and weight is unknown and has disappeared into the archives.

Claire Halpin. A Dead Horse This story is one my mother has often told me of her mother - My mother had experienced unemployment, tenement living and poverty, common to many living in north innner city 1900’s Dublin. Tailoring was her job but work was scarce. She would be classed as an alteration hand and collected garments for adjustments. These were done at home in Mountjoy Square and returned completed to various outfitters – Kingstons, O’Beirne and Fitzgibbon etc. It was on her way to work on Tuesday morning 24th April 1916 that she became aware of something strange afoot in Dublin. On that particular morning as she rounded the corner from Parnell St. onto O’Connell St. walking towards Findlaters she saw a dead horse on the road. As she told it herself “her dream was out” – attaching great significance to the recent ominous dream she had had of a fallen horse. This is how she first became aware of the unfolding events of the 1916 Rising. Máirín Halpin (neé Taylor)

Constance Short Cailíní na hÉireann As is emerging in recent years many women were involved in the Easter Rising of 1916. I was amused to read that they had to cook, tend to the wounded as well as act as soldiers and messengers between the Irish garrisons. They wore nurse’s uniforms so they could move freely through the city. They carried messages and ammunition under their skirts. Women multi-tasking is not just a modern day phenomenon!! Women had to “Juggle” then, as they do now. Only women officers were allowed use guns and they tended to come from the upper classes. The “regular” women volunteers were referred to often as cailíni, instead of mná. My piece is a tribute to them.

Constance Short Take Note Many hastily written notes were written between the garrisons and delivered by woman volunteers who for decades remained anonymous. This piece is a reflection of that. These brave women volunteers risked their lives ducking British bullets in keeping these lines of communication open. None braver than Sheila Grennan and Elizabeth O Farrell who were with Padraig Pearse in the GPO. This piece is dedicated to them and especially Elizabeth who braved out with the flag of surrender on Saturday 27th

Constance Short Surrender Only recently it was discovered that there was a woman involved in the 1916 surrender. On Saturday 27th April 1916, Commandant Padraig Pearse asked Volunteer Elizabeth O’Farrell to go out with the white flag of surrender to Brigadier Lowe of the British Army. Lowe refused to negotiate with a woman and asked that Pearse come himself. Elizabeth O’Farrell then accompanied Padraig Pearse, again carrying the white flag, and there is a formal British Army photograph of the surrender. It contains Padraig Pearse, Brigadier William Lowe and his aide de camp and son John Lowe but no Elizabeth O’Farrell. She had been airbrushed out of the photograph apart from her feet. This photograph is in Kilmainham Jail. My lino-cut takes the photograph quite literally, replacing Elizabeth O’Farrell where she rightfully belongs.

Deirdre Shanley Armoured Lorry The first tanks were used by the British Army at “the front” in June 1916. In April, two months earlier, in Dublin, two very different styles of “tanks” were constructed in haste during the 1916 Rising, to transport soldiers and equipment. The raw materials for the armoured cars consisted of Daimler lorries borrowed from the Guinness Brewery, as well as a number of locomotive boilers and an amount of steel plate. I chose to depict the more straightforward box-like design in my print. The steel plates used in this arrangement remind me of the bed of the printing press. The tanks played an important role in the success of the British forces’ defeat of the rebels. They could hold up to twenty-two men and had slits cut into the steel for air and to fire out of. Eventually the Daimler lorries had their armour removed and they were sent back to Guinness to resume their job of delivering stout.

Dominic Turner Fireworks, Easter Monday 1916 Several sources refer to the looting that took place on Sackville Street, Easter Monday, 1916. One of the most targeted shops by local children appears to have been Noblett’s sweet shop and Lawrence’s toyshop. Amongst the toys that were looted by the children from Lawrence’s was an amount of fireworks, which produced both joy and tragedy. ‘A member of Fianna Eireann, Eamonn Bulfin, watched Lawrence’s from the roof of the GPO as ‘all the kids brought out a lot of fireworks… and set fire to them.’ He recalled the volunteers’ own bombs on the roof of the GPO as rockets ‘were shooting up in the sky. We were nervous. There were Catherine Wheels going up Sackville Street.’

Dorothy Smith Looking Through 1 Nellie Gifford, Madeleine Ffrench Mullan, Rosie Hackett, Kathleen Lynn, Winifred Carney, Marcella Cosgrove, Eilis Ní Riain Looking through layers of time and change back to the tumultuous events of 1916, the role of women is belatedly but eventually being acknowledged. The seven women my prints are based on were engaged in public life at a time when the consensus was that women’s only role was in the private home. Working from old photographs and layering the drawings, I have created a composite image that is not of each individual person but is an image of women then looking through time at us now, what has been achieved. How much we owe them.

Dorothy Smith Looking Through 2 Nellie Gifford, Madeleine Ffrench Mullan, Rosie Hackett, Kathleen Lynn, Winifred Carney, Marcella Cosgrove, Eilis Ní Riain Looking through layers of time and change back to the tumultuous events of 1916, the role of women is belatedly but eventually being acknowledged. The seven women my prints are based on were engaged in public life at a time when the consensus was that women’s only role was in the private home. Working from old photographs and layering the drawings, I have created a composite image that is not of each individual person but is an image of women then looking through time at us now, what has been achieved. How much we owe them.

Eileen Keane Cards and Guns Liam Archer was a member of the I.R.B and in Easter week 1916 he and men from his company were guarding the Keating Branch, 18, North Frederick St. where some members of the Volunteer executive were living on the run. On Easter Sunday night one man was on guard in the hall and the rest were in a small room overlooking the hall. They passed the time playing cards. Michael Collins had been out at the Larkfield estate of the Plunketts helping with the military preparations and he arrived in North Frederick St. According to Archer: ‘He forced his way to a seat at the table, produced two revolvers and announced he would ensure there would be nothing crooked about this game.’ Meanwhile Christopher Brady, a printer who worked for the ITGWU, helped by Michael Molloy and Billy O Brien, was busy printing the Proclamation of the Irish Republic in the basement of Liberty Hall. They had a dilapidated press and when they ran out of letters they used other fonts and even made letters from sealing wax.

Eileen Keane Stop the fighting On Wednesday 26th April 1916 thousands of soldiers from the 59th division landed at Kingstown (Dún Laoghaire). A 2000 strong column marched towards the city. Mount St. Bridge was guarded by a platoon of Volunteers under Michael Malone. The British soldiers were slaughtered as they tried to push forward, and it took 30 hours of fierce fighting before they captured the bridge. In the middle of the fighting a teenage girl, Louisa Nolan, ran out onto the bridge with bullets flying on all sides, calling for the shooting to stop. The Volunteers stopped firing and the British followed suit, while Louisa and another woman carried a wounded soldier to safety and others came forward to help them. Then a group of doctors and nurses from St. Patrick Duns hospital came forward with a Red Cross flag to bring the wounded to the hospital nearby. Louisa Nolan was presented with a Military medal at Buckingham Palace on 2nd February 1917 in recognition of her heroic action.

Fifi Smith “I don’t know how I did it” ‘The changes that convulse society do not appear from nowhere,’ writes the historian Roy Forster in his book Vivid Faces: the Revolutionary Generation in Ireland (1890-1923). He continues ‘They happen first in people’s minds, and through the construction of a shared culture...’ While reading this, I thought of Dr. Kathleen Lynn’s account of the Citizen Army’s occupation of City Hall in 1916. She noted that when she arrived as part of the occupying force she found “The gate of the City Hall was locked and I had to climb over it, though I don’t know how I did it.” This print symbolises that tiny moment of strength, which she needed to find within herself. It showed me the importance of the previous decades of cultural revival before the rising which gave strength to a small number of ordinary individuals to do courageous acts when the final bid for independence erupted in 1916.

Fiona Marron Chaos Chaos reigned all over the city. One of the most tragic cases among the civilian casualties of the 1916 Rising was that of Francis Sheehy Skeffington who was murdered while in military custody. Born in Cavan in 1878, Skeffington married Hanna Sheehy, from a notable Co. Cork nationalist family. As a token of his commitment to equality of the sexes he adopted her surname, thereafter calling himself Sheehy Skeffington. The couple worked together for a number of socialist and radical causes, including women’s suffrage. He co-founded the “Irish Citizen” in 1912. Sheehy Skeffington was a pacifist and campaigned against recruitment following the outbreak of WW1, thereby receiving a sentence of six months imprisonment. He supported Home Rule and disapproved of the increasing militarism of the Irish Volunteers. He tried to impress on Pearse and Connolly that civil disobedience was a more powerful weapon than rebellion. He was so concerned at the scale of looting he organized a citizens’ police force to maintain law and order. On Tuesday of Easter week, while out walking, he was arrested in Rathmines, for no apparent reason. He was detained in Portobello Barracks. The next morning he was shot at the behest of Major Bowen Colthurst. Due mainly to the intervention of a conscientious senior officer, Colthurst was court-martialed, found guilty but insane. Hanna Sheehy Skeffington refused to accept monetary damages awarded subsequently.

Ger Kennedy Limbs that had run wild “Too long a sacrifice, Can make a stone of the heart, O when may it suffice? That is Heaven’s part, our part To murmur name upon name, As a mother names her child When sleep at last has come On limbs that had run wild. What is it but nightfall? (From Easter 1916, W B Yeats)

Geraldine O’Reilly The Moment of Surrender Elizabeth O’Farrell was the woman asked to escort Padraig Pearse to Britain Street where he surrendered to Brigadier General Lowe on the 29th April 1916. I remembered there was always talk about the photograph of the event. In some photographs one can clearly see her feet standing behind Pearse. In other photographs she is missing. Were there several photographs of the event? Or was she airbrushed out of history? In my print I remade the image of Elizabeth standing behind Pearse. I also remade the letter she carried to Pearse from the Brigadier General, asking him to surrender. Working with a magnifying glass in order to draw the images onto copper plate – I was moved by the poignancy of the event knowing the outcome.

Jennifer Lane Off to War Tram cars to war: In times gone by, soldiers marched to the battle fields, or travelled on horseback, trains or trucks. But during the 1916 Rising, some of the Volunteers simply cycled into the city on their bikes, others just hopped on to one of the many trams which criss-crossed Dublin in those days, on their way to the General Post Office in Sackville Street.

John Curran Whisper it 1966 was the 50 years commemoration of 1916 and its events and outcomes figured greatly in the history taught that year in National school. I was then 8 years old: the story and personages of the Rising, and the public celebrations and media coverage of it had a powerful effect on one's perception of those events. The element of sacrifice, of dying for Ireland's freedom and the pain and tragedy of it all for its protagonists added a big emotional charge to the historical facts - it is this felt dimension to the stories we as schoolchildren ingested about bravery, hopelessness, tyranny, glory and so on that came back to me when remembering that time in 1966 when the celebration of the Nation was visceral and unambiguous. During Easter 1966 our mother took us to Offaly to visit our grandparents and while we were down there a visit was made one afternoon to an old lady who lived some distance away, the other side of Tullamore. This old lady lived in a traditional thatched house, the paintwork deep green, a fire burning in a wide fireplace on a huge hearth, and the scent of the smouldering peat was very, very strong . The old lady, whose name I never knew, was talking to the adults about 1916 which she remembered well, and the old house, the turf fire and its aged owner had for the 8 year old me a sense of Ireland past, still alive, real andalpable - as though the vivid history lessons in school that had brought one close to gunfire, death and sacrifice in the GPO had spilled out beyond the classroom. But what really triggered these sensations, which are still vivid 50 years later, and which are the story that inspired my print, was a calendar on the wall in this old, smoky, definitively Irish house, the month illustrated with an image of the GPO in flames, and a warrior brandishing a Celtic sword in the foreground, depicted in pure, heroic, sacrificial white against a green red and orange ground, the flames stylised and vibrant. It was a visual summation of the terrible beauty that our schoolteacher had somehow imbued the Rising story with. I expect the image in that calendar was originally a lino print from the 1920s, given its stylism, its didactic clarity, so archaic and angular when reproduced in 1966. And though I have searched in archive and album for it in these past months, it has had the decency to remain, like the exact particulars of the Past itself, elusive.

Katherine Smits Decoys 12 men on bicycles were sent out as a ‘diverting party’ from the Garrison at Jacob’s biscuit factory to draw the attack off Boland’s Mill. 1 cyclist Volunteer rebel died. Also during the week of the 1916 Rising 40 children died, 318 civilians died, 50 rebel volunteers died, 7 Irish rebel leaders died, 130 British soldiers died They died either by execution, bombs, gunfire or by being caught up in violent sieges causing ‘collateral damage’ as its known today. Why in 2016 do we still condone and commemorate violent events?

Margaret Becker Animal Magic My print illustrates a recorded event, which took place every day during the assault by the Volunteers in St. Stephen’s Green on the British who were occupying the Shelbourne Hotel. At a given hour all warfare ceased in order that the ducks might be fed. When the fighting took place between the Volunteers and the British army, the Volunteers were in St. Stephen’s Green and the British soldiers were in command of the Shelbourne Hotel. The British army snipers were positioned on the rooftops and in the windows of the hotel while the Volunteers dug trenches in the Green and engaged the enemy from this position. Meanwhile, the Keeper of St. Stephen’s Green continued to feed the ducks who made their home on the pond in the green. They were fed every day at a given hour. The marvelous keeper who performed this duty ignored all the warfare and dutifully fed the ducks at the appointed hour every day during the battle. It is said that both sides honored this occasion by stopping the shooting while the ducks were being fed. Hopefully they thrived, as alas many of the combatants didn’t. Such is war, the sensibility of animals or the power of nature!

Margaret Becker No Need to Sharpen Inspired by an account of the event read in “Noontide Blazing” by John Cowell. (Title taken from a Michael Collins’ poem) When Cumann na mBan were feeding the Volunteers in one of the 11 posts around Dublin City, they made endless sandwiches and cups of tea and people brought them food from where ever they could get it, a leg of mutton arrived one day and not a knife was around to carve it, so one member of Cumann na mBan, a medical student in fact, seized a bayonet from a bewildered Volunteer and proceeded to carve the meat and make sandwiches, the Volunteers were very well fed thanks to Cumann na mBan.

Margaret Irwin Bullets Draw Blood I grew up at a time when Michael Collins had been completely “written out” of the history books except as a failed negotiator. Having been born in India, where my Roscommon-born father worked as a civil servant all his life, I think of how India won her Independence, peacefully. It took a very long time and much dedication. I dare to wonder, if Michael Collins had not died, would he, perhaps, have proved to be our “Gandhi”?

Margaret Tuffy Dawn On April 29th the revolutionary forces took final leave of the GPO by the side door on Henry Street. Leaving in groups of three, they crossed the road to Henry Place and Moore Lane, their intention was to join their comrades at the Four Courts. Unaware that the British had erected barricades at different junctions in this area, the rebels were taken by surprise and sought shelter where they could. Under fire at the junction of Moore Lane, where a barricade was in position, they forced their way into 10, Henry Place, by shooting the lock off the door. Thomas McKane and his 16-year-old daughter, Bridget, were standing behind the door. Thomas was injured in the hand and Bridget took a bullet in the head. She died shortly after. Her mother Margaret was with her at her moment of death and her signature is on the death certificate. SURRENDER Dawn is creeping in Silently, as the waning moon. The night-truce tipping into broken A child cries, someone whistles, I have known the impact of it. My mother’s mourning fills me Hope upon hope, a tangible force. An ancient plea, for time, for mercy, A mantra whispered in my ear Then, a low keening of surrender.

Melissa Cherry Allsorts Allsorts’ was the winner of the 1916 Grand National. The Grand National was held at Fairyhouse racecourse in Co. Meath. Richard Cleary trained ‘Allsorts’. He was owned by Mr. James Kiernan. When news of the Rising got to the racetrack all roads where blocked, trains and buses were cancelled. It took some people over a week to get home. Like Mr. Joseph Devin’s, a shopkeeper from Co. Clare. When he walked in the door of his house, his wife thinking he was dead, took fright at his arrival. As for the winning racehorse ‘Allsorts’, he had to walk home after the race without any celebrations. There are no photographs of the horse at Fairyhouse so maybe someone might have a photograph of this forgotten animal.

Michele Sweetman And the Poppies grew free in 1916 I am not a fan of violence, although I recognise tough measures have to be taken in tough times. Sometimes. As the poppy is a controversial flower in Anglo-Irish relations, a petal is used by British military to remember those who lost their lives fighting in wars, many, many of them Irish souls! Perhaps the poppy could become a symbol of what we share living on these islands, near but separate to mainland Europe, so vastly intertwined are we. I tend to balk at the notion of celebrating a violent time with all the agitation, promoted by memory, leaving people stuck in ideas relevant to another time, feeling less than proud of being Irish at present, after all the “muck savagery” of the Celtic Tiger years, the greed, excess waste, selfishness, total irresponsibility... I feel we are a very immature nation, all too quick to blame others for our misfortunes. We need to grow up, take responsibility, and show decency to our fellow Irish people! Let’s let go of the injustice of the past, stop blaming others for our own inadequacies, look after our own and appreciate what we share with our neighbours! Poppies still grow wild and free on our island, as they did in 1916, as it does on all these islands!! Peace!!!

Mo Montgomery Kilcoole Landings One of the most important (and little known) events in the arming of the Volunteers occurred on 1st August 1914. The yacht ‘Chotah’ was loaned by Sir Thomas Myles to the triumvirate mission leadership of Michael the O’Rahilly, Erskine Childers and Sir Roger Casement. Having an engine enabled the yacht to land close to the shore and arrange an accurate nighttime arrival. Some six hundred rifles (of Prussian origin) and 20,000 rounds of ammunition were safely unloaded and hidden. (Reference article by James Kirwan and booklet published by Kilcoole Heritage Group in July 2014.)

Monica de Bath i láthair/Present Lily O’ Brennan, Cumann na mBan, kept a diary during Easter Week 1916. On her way to Richmond Barracks she tore it into little pieces to protect those named in her record. The torn up diary gives weight to the sense that significant acts disappear from the official record. Her diary (Mountjoy 1923) records her shifting between a depressed state and an assertive state. Written partly in pencil, now faded, it is difficult to read. ‘i láthair / present’ – references these diaries and imagines an entry, both written and painted, that notes the move from a free to an imprisoned space for women, actively involved in the 1916 rising. It shows a roll call of some who were imprisoned in Kilmainham, Mountjoy or Richmond Prison. An illegible layer beneath the top layer holds other names - Winifred Carney, Josie Mc Gowan, Kitty Maher, Máire Perolz, Nora O’ Daly, May Gahan, Nell Humphreys, Helena Molony, Rose Mc Namara.

Morgan Doyle A Cross for each County This is a personal story, which relates to a visit I made to Kilmainham gaol in 1975 as a schoolboy. It is a visit that I remember with clarity, for what reason? My childish fascination was that James Connolly had been strapped to and shot in a chair, an extraordinary thing. When visiting the cells I looked at vague scratching on the walls of the cells and tried to decipher what I thought must be hidden messages. On return home I wrote an essay suggesting that I had deciphered the text on the wall. That the chair was to taken apart and reassembled into 32 crucifixes, in memory of their fight and they be painted white as a sign of peace, placed in each county so people would remember. These would be small and unassuming and remind us that people are capable of extraordinary things. These are my 32 white crucifixes.

Pauline Keena The Baby Shoes Kathleen Clarke, wife of Thomas Clarke, a signatory of the Proclamation and subsequently executed for his part in the Rising, was a founder member of Cumann na mBan. They had three children together. Thomas Clarke forbade her to have an active part in the Rising. Pregnant on her 4th child she visited her husband in prison before he was executed. She lost the baby shortly afterwards. She set up the Irish National Aid fund to help the families of those executed or imprisoned after the Rising and she became an active member of Sinn Féin. In 1918 she as arrested and imprisoned for 11 months in Holloway, England where she made infant shoes.

Paul Roy Eugene Prepares for the Big Day Porter, Eugene (Owen). Staff Officer, General Headquarters, Irish Volunteers. Born in 1897 died on the 25th of January 1962, Eugene was aged about 19 years old during the Rising. He fought in the areas of Bath Avenue Bridge, Railway Line between Westland Row and Lansdowne Road, Boland’s Bakery/Boland’s Mills and Grand Canal Street. Prior to the Easter Rising, Eugene Porter had served as a Battalion Signal Instructor and after his release from prison he assisted in the reorganisation of the Irish Volunteers in County Wicklow. He was a delegate to the Irish Volunteer convention in 1917 as well as a Battalion Officer Commanding. He served with the Defence Forces as a Private in 3 Field Company, Supply and Transport Corps in the 1940s during the Emergency (Second World War). The print is an image of a young mans pensive and measured in preparation for a momentous occasion. Eugene Porter is the grandfather of my wife, Sandra Porter-Roy.

Paula Fitzpatrick Among the Rising drills My “Little Story” is about my great, great, grandmother Elizabeth O’Connor, a formidable lady, who lived in the Dublin Mountains during the period of the 1916 Easter Rising and the Irish Civil War, where she owned Ballyboden House, and other properties and land in the area. Her two granddaughters Catherine and Elizabeth Doyle were my maternal grandmother and grandaunt. Gran and Aunty, as I called them, were brought up by Elizabeth O’Connor following the early death of their mother Teresa Doyle, nee O’Connor. One of the stories I overheard as a young girl was when word came one evening that the brutal Black and Tans were about to raid Ballyboden House, where a small group of Republican fighters were meeting. Elizabeth O’Connor saved them by hiding them in the potato drills in the field behind the pub. My research continues into many similar stories about her.

Rachel Fountain John At 7am on Thursday 27th, the small body of John Francis Foster aged 2 years and 10 months, was the first victim of the 1916 Rising to be buried in Glasnevin Cemetery. By his side was a single mourner, his grandfather, who watched, as the child was laid to rest in the family plot. His mother Catherine ‘Kate’ Foster was not permitted to attend her son’s burial, as martial law had been declared on the city. This was the second tragedy for a grieving Kate, whose husband John from Ballymore Eustace, Co. Kildare had been killed on the Western front only a few months previously. Witnessing the shooting of her son left an eternal impression on Kate, who, for the rest of her life, kept a treasured memento with a photograph of young John on one side and her husband John on the other. Kate Foster died on 6th February 1964.

Rebecca Homfray Moore Street The idea for my print came to me after some fellow printmakers and I were taken on a walking tour around Dublin to educate us about the events leading up to the 1916 Easter Rising. This tour was a great help to me, as I have no background in Irish history. We finished our walk in Moore Street on a bright, blustery afternoon to be told about the fighting, the flying bullets, the wounded men, the call for retreat, the confusion and fear. It all seemed so improbable and a world away as we wandered down the street through the now bustling fruit and vegetable market.

Ruby Staunton Of what is past or passing or yet to come Marsh’s Library, situated between St Patrick’s Cathedral and Jacobs Biscuit Factory, became an unwitting participant in the violence that occurred during the 1916 rising. Established three hundred years ago, the Library is one of the few buildings in Dublin to retain its original purpose. On the Easter Sunday of the Rising the building was sprayed with bullets, literally, being in the line of fire. The Biscuit Factory had been requisitioned by the rebels and British troops stationed in St Patrick’s Park across the road from the library fired on the building, damaging doors and windows, penetrating the books lined upon the shelves inside. Many of the books were shredded internally as a result of bullet entry and exit, rendering them unreadable. This print is a representation of the idea of how we can imagine the damage a bullet can inflict on human flesh and how during the Rising many people suffered the same fate, albeit with more formidable results!! (Story source: Keeper and staff of Marsh’s Library)

Shane Crotty Aos Sí Maud Gonne MacBride was a political activist, actress and suffragette. The daughter of an English army officer, she became financially independent after his death. She became involved in French republicanism and had a child with a French politician. The child died in infancy. A story emerged that she tried to subsume the soul of her dead son into another child by conceiving on top of the tomb. This was how her daughter Iseult came about, according to WB Yeats. Maud Gonne was influenced heavily by mythology and mysticism. She was briefly a member of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, a group that mixed ceremony, ancient mythologies with the occult and fantasy. She campaigned for prisoner rights and the nationalist cause. A founding member of Inghinidhe na hEireann, its main aims were furthering Irish independence, encouraging the Irish language, its arts and history while simultaneously discouraging the cultural influence of Britain. She married Major John MacBride, one of the executed after the Rising. The Aos Sí or Tuath na Danann were a mythical race from the early records of Irish, Scottish and Isle of Man folklore. The term translates into ‘People of the Otherworld’ although the original meaning and origin is open to interpretation. It also meant the home of the gods or a type of afterlife for mortals particularly favoured by the gods. This piece is a reflection of Maud Gonne’s interest in mysticism and, framing it in the context of the 1916 rebellion, I feel she and Yeats were aware the myths and legends around this period of Irish history would endure and shape our society.

Siobhan Cuffe Fág an Bealach/Out of the way In 1916 my 34-year-old grandmother, Margaret Little lived in St. Mary’s Road beside Mount St Bridge with her husband and 2 small children. Margaret was born into a political family. Her grandfather had left Ireland in a hurry at the time of the 1803 Emmet Rising. Her father was born in Prince Edward Island and moved to Newfoundland with his older brother where they established the first Catholic law practice. He later became the first elected Premier of Newfoundland before he married an Irish bride and came back to settle in Dublin. In 1900, Margaret was sent home for the day when Queen Victoria visited her school, Mount Anville, as she made it known that she would not curtsey to the Queen. On Easter Monday 1916 Margaret and her husband Laurence Cuffe went to Fairyhouse races. They had a good day but heard of trouble in the city and left their car in Smithfield to walk home via Rathmines. The Cuffes, a family of cattle dealers are recorded as being in business from the 1820s in Smithfield. During the week Margaret heard that her brother Paddy Little, editor of ‘New Ireland’ had been arrested. Margaret was very close to Paddy, who was a solicitor and a journalist. Margaret got on her bike and went to the Archbishop to ask the authorities to get him out. She succeeded.

Siobhan Hyde IV The seven bullets represent the seven leaders of the Easter Rising. Thomas J Clarke , Sean MacDiarmada, Thomas Mac Donagh, P.H. Pearse, Eamonn Ceannt, James Connolly, Joseph Plunkett. In 1914 Home Rule was granted to Ireland but was postponed due to the Great War. The IRB and Irish Volunteers staged a rebellion on Easter Monday, 24th April 1916. Irish forces mainly used German weapons and ammunition including the 1871 Mauser rifles, many of which were part of the arsenal brought to Howth by Erskine Childers in 1913. British forces used the Lee Enfield .303 rifle The seven were tried under martial law during time of war and executed. Public opinion was originally against the Rising but their execution brought about a change in attitude leading eventually to the War of Independence and ultimately to the foundation of the Irish Free State in 1921.

Suzannah O’Reilly Surrender When researching this project I came across the letter of surrender by Padraig Pearse from the 1916 Easter Rising. It was written on card from the back of an old picture frame and Elizabeth O Farrell, carrying a Red Cross flag delivered it to the British Forces. I was attracted to the composition of the letter on the website which was similar to a flag as well as the colour and the texture of the card. The final image echoes a cross, which symbolises Padraig Pearse sealing his fate when he wrote the letter of surrender.

Sylvia Hemmingway, 25 Minutes 21 Seconds In 1916 time and times in Ireland changed forever. When the G.P.O. clock stopped at 2.25 p.m. during the Easter Rising of 1916 it was operating under Dublin Mean Time. ‘London Time’ was 2.50 p.m. (G.M.T.) at that moment. The Statutes (Definition of Time) Act of 1880 defined Dublin Mean Time as the legal time for Ireland. This was the local mean time as measured at Dunsink Observatory, where sunrise and sunset were 25 minutes and 21 seconds later than at Greenich Observatory in London. James Joyce mentions ‘Dunsink time’ five times in his novel Ulysses. Later in the year the Time (Ireland) Act 1916 defined the legal time for Ireland to be Greenich Mean Time and time changed in Ireland at 2:00 am Dublin Mean Time on 1st October 1916. When British clocks went back an hour for winter on Sunday, 1st October 1916, Irish clocks went back by only 35 minutes to synchronise clocks in Ireland and Britain. There was some opposition from local councils, politicians, farmers and some business groups. Countess Markievicz complained bitterly about the change, writing that “public feeling was outraged”.

Val Hennigan Caws of Alarm The loss of life and physical devastation of the city of Dublin in the 1916 Rising brought to mind a poem by Thomas Merton “Fable for a War” The poet’s words inspired this image, “Caws of Alarm ““And in the end of all, Crows will come back and sing the funeral.

Val Hennigan The Foggy Dew As down the glen one Easter morn to a city fair rode I There Armed lines of marching men in squadrons passed me by No fife did hum nor battle drum did sound its dread tattoo But the Angelus bell o’er the Liffey swell rang out through the foggy dew Right proudly high over Dublin Town they hung out the flag of war ‘Twas better to die ‘neath an Irish sky than at Sulva or Sud El Bar And from the plains of Royal Meath strong men came hurrying through While Britannia’s Huns, with their long range guns sailed in through the foggy dew ‘Twas Britannia bade our Wild Geese go that small nations might be free But their lonely graves are by Sulva’s waves or the shore of the Great North Sea Oh, had they died by Pearse’s side or fought with Cathal Brugha Their names we will keep where the Fenians sleep ‘neath the shroud of the foggy dew But the bravest fell, and the requiem bell rang mournfully and clear For those who died that Eastertide in the springing of the year And the world did gaze, in deep amaze, at those fearless men, but few Who bore the fight that freedom’s light might shine through the foggy dew Ah, back through the glen I rode again and my heart with grief was sore For I parted then with valiant men whom I never shall see more But to and fro in my dreams I go and I’d kneel and pray for you, For slavery fled, O glorious dead, When you fell in the foggy dew.

William Finnie January 1916 For three days in mid January 1916 James Connolly went missing. His Transport Union colleagues in Liberty Hall and his family thought that he had been “lifted” by detectives from Dublin Castle. The British Administration in Dublin and London regarded Connolly as one of the most dangerous of the many agitators active in Dublin at that time. In fact he had been “kidnapped” by the IRB Military Council and taken to a safe house in Dolphin’s Barn. For three days he met and argued with Joseph Plunkett, Patrick Pearse and Séan MacDiarmada. They convinced him not to proceed with the threatened Irish Citizen Army Uprising, but to join the ICA with the Irish Volunteers in the planned Easter Uprising. At the end of the three-day meeting Connolly became a member of the IRB Military Council. This meeting in January 1916 had profound implications for the future of Socialism and Social Democratic Politics in Ireland.